Overconfidence in CCS setting us up for disappointment

After near-total failure 15 years ago, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is once again being hailed as the climate saviour. However, recent research published in Nature reveals sobering insights—this technology, still in its infancy, is unlikely to scale in time to meet climate goals.

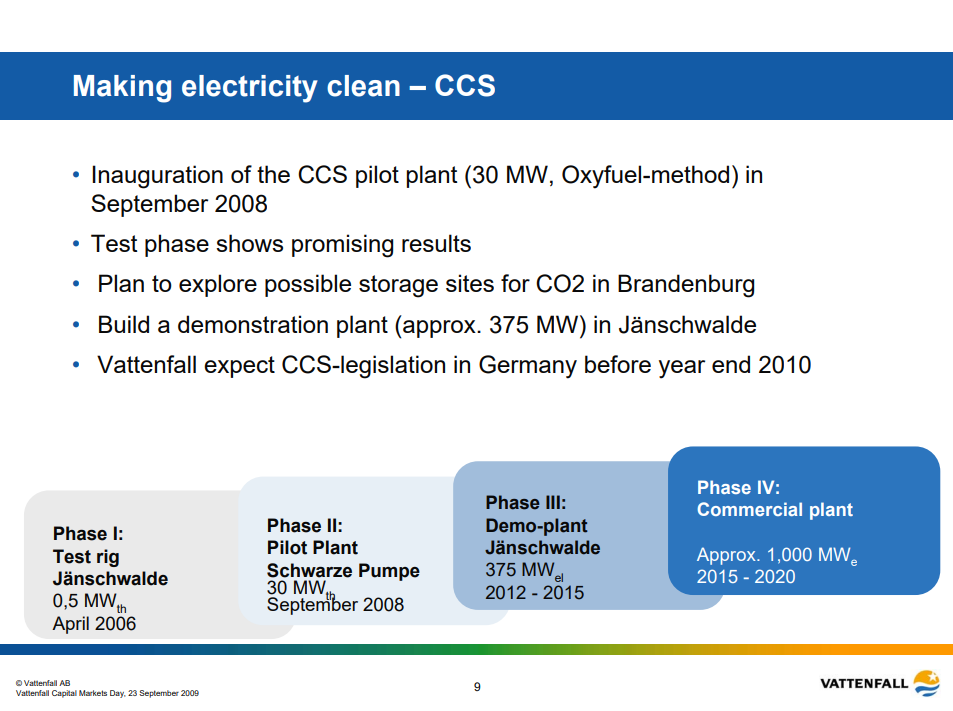

I remember talking to Vattenfall's then-CEO, Lars G. Josefsson, at their CMD in Amsterdam in September 2009. He was religiously convinced that the company's increased climate footprint through the purchase of Nuon could be counteracted by the company's CCS project. Back then, in 2009, they expected the first facility to be up and running at full capacity of some 1,000 MWe sometime between 2015 and 2020. I remember thinking it sounded too good to be true even then, and of course, it was. So is it different this time around?

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is often presented as a key technology in the fight against climate change, hailed as a potential solution to slow the rise in global temperatures. But is this technology really the silver bullet it’s made out to be? Despite years of research and development, progress remains slow, and the ambitious targets set by global climate agreements seem increasingly out of reach.

In a recent analysis published in Nature Climate Change, researchers from Chalmers University and the University of Bergen sound the alarm: CCS, at its current pace, will not meet the demands of global climate targets. For investors and business leaders banking on the technology’s success, this raises important questions: Can carbon capture ever scale to the level needed, or is it just another overhyped climate solution that’s destined to disappoint?

Bold Claims, Slow Results

CCS technology works by capturing carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes and power generation and storing them underground. Theoretically, this could mitigate significant emissions from industries that are hard to decarbonise. However, despite the hype surrounding CCS, the numbers tell a different story.

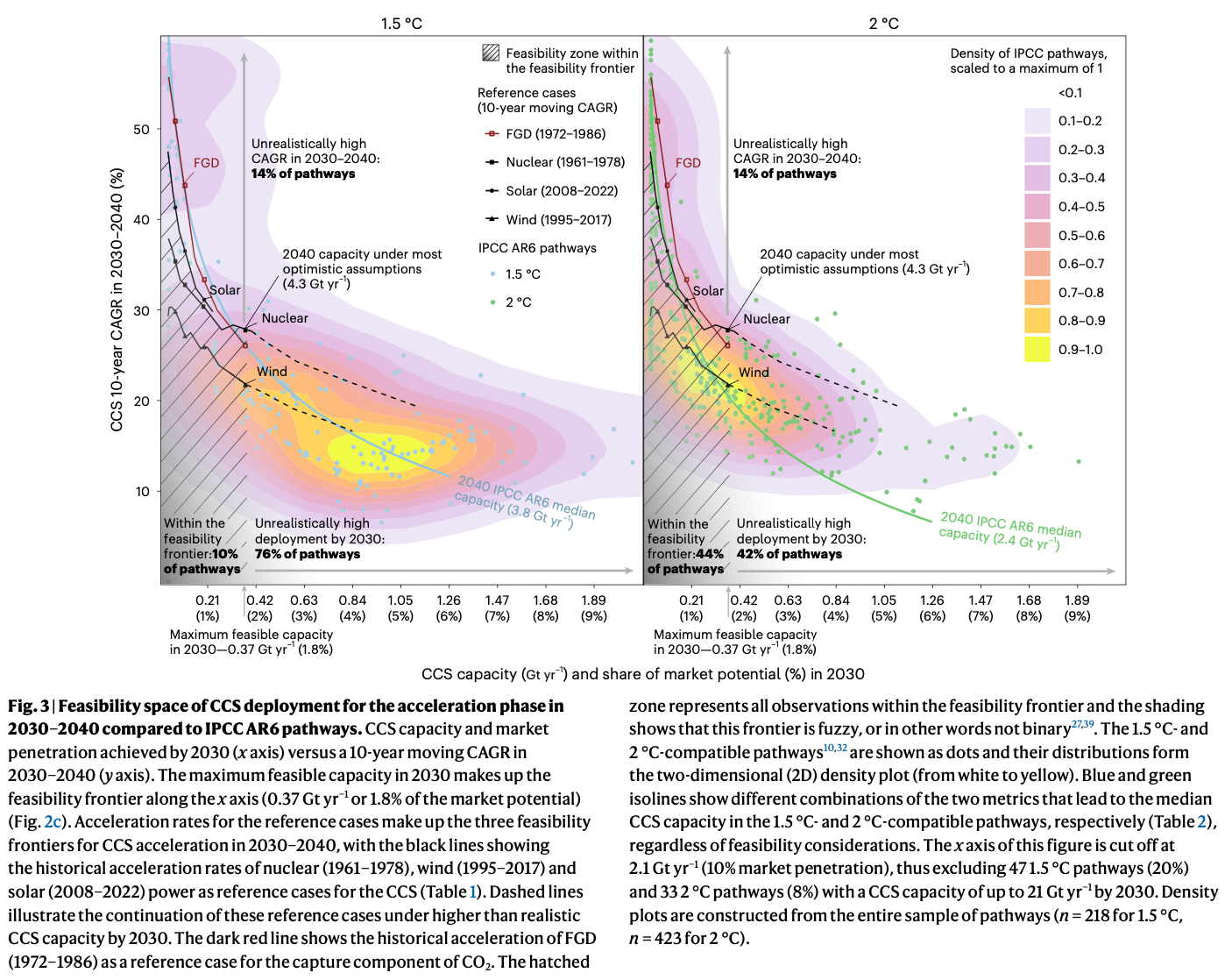

The UN's climate panel, IPCC, has long positioned CCS as essential to staying below the critical 2-degree temperature rise. But, according to the Nature study, even the most optimistic projections suggest CCS capacity will only reach 0.37 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2030. That’s well short of what’s needed for a 1.5-degree pathway.

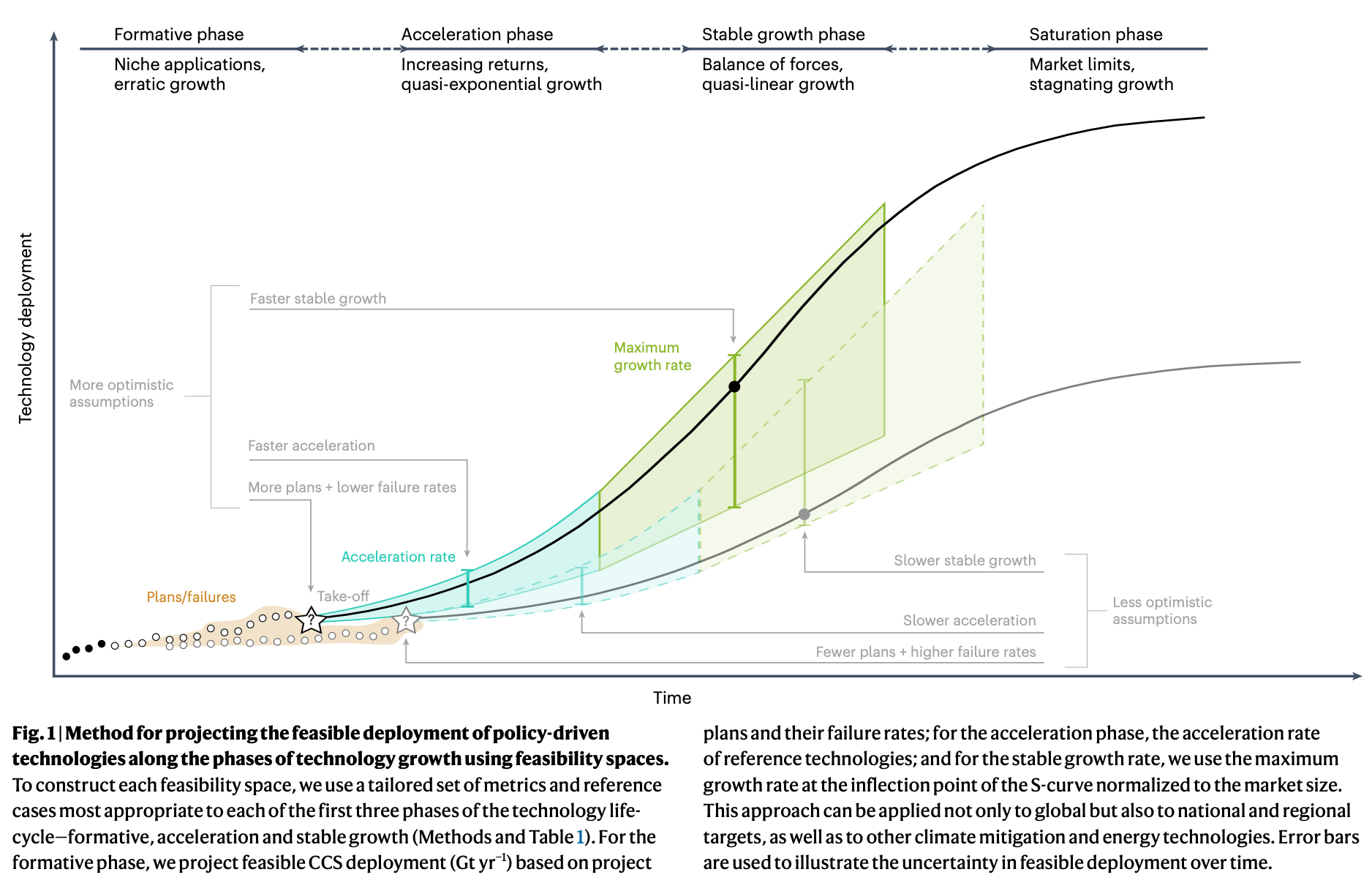

The real challenge is how slowly this technology is advancing. While other clean technologies like wind and solar have managed to ramp up production rapidly, CCS remains stuck in the formative phase. To meet climate targets, it would need to grow at an exponential rate—comparable to the rise of wind power in the 2000s or nuclear power in the 1970s and 80s. But experts warn that this kind of acceleration is unlikely, if not impossible, to achieve.

Investors Beware

The history of CCS is littered with failed projects. According to the Nature Climate Change study, nearly 90% of early CCS initiatives from 15 years ago fell through. While today’s portfolio is more diversified, with a greater variety of applications, the technology still faces significant hurdles—chief among them, cost and implementation delays.

For investors, this should serve as a stark warning. The promise of CCS is enormous, but so are the risks. In its current state, CCS remains a capital-intensive and risky venture, with many projects still struggling to move beyond the idea stage. While some bold investors might be willing to take the leap, banking on the technology’s eventual success, it’s a gamble that requires careful consideration.

Moreover, CCS is far from being a market-driven technology. It requires substantial policy support, which means any progress is likely to be dependent on government intervention. Without strong political backing in the form of subsidies or stricter carbon regulations, CCS may continue to stagnate, leaving investors holding the bag.

The Harsh Reality of Climate Targets

The study published in Nature makes one thing abundantly clear: CCS alone will not save us from climate catastrophe. Even if CCS projects were to ramp up at the most optimistic rates, the total amount of carbon stored by the end of this century would likely be no more than 600 gigatons—far less than the 1,000 gigatons some climate models have called for.

As Jessica Jewell, one of the researchers, bluntly states: "Even 600 gigatons is an ambitious target, but it’s still likely the upper limit of what we can realistically achieve." The takeaway for investors is that while CCS may have a role to play in future mitigation efforts, its potential to meet the scale of demand required for climate goals remains highly uncertain.

A Missed Opportunity?

As we edge closer to 2030, the window for meaningful climate action narrows. The world may have pinned too many hopes on a technology that simply cannot scale fast enough to make a difference. The urgency to decarbonise remains, but it may be time for business leaders and investors to question whether CCS can truly deliver on its promises—or whether it’s time to focus on more viable, scalable solutions.

For now, CCS looks more like a speculative bet than a surefire climate solution. Investors who are waiting for a breakthrough may find themselves disappointed, as the technology’s slow growth continues to fall short of its lofty expectations.